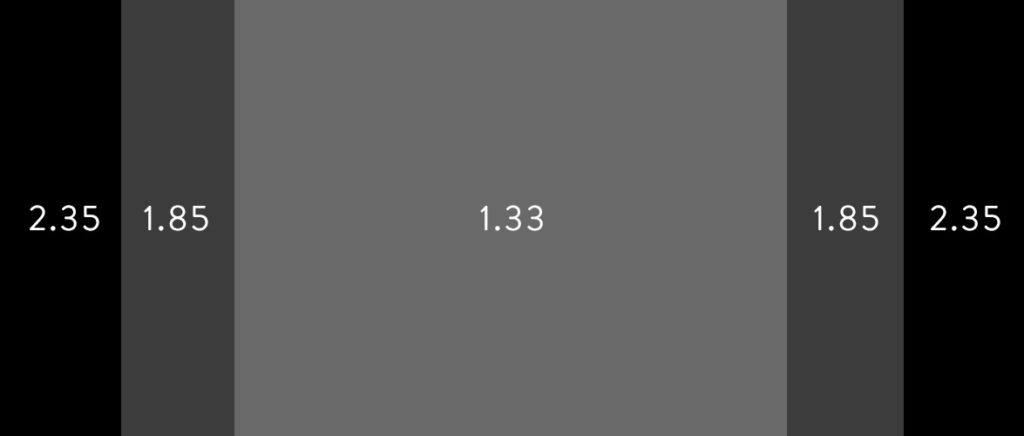

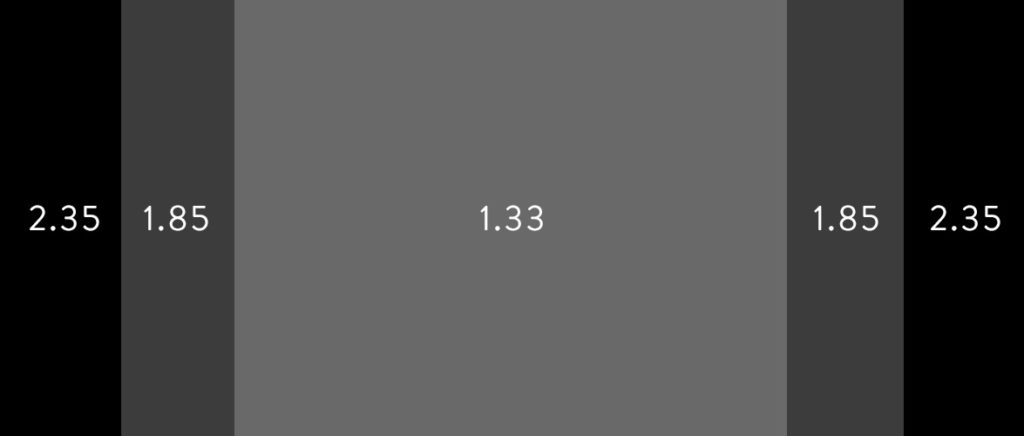

For years, the classic 4:3 (or 1.33/1.37) aspect ratio has been on life support. What was once the standard aspect ratio of motion picture film, began to fizzle out as early as the 1950’s when various widescreen formats were introduced, such as cinemascope.

But even as film moved away from 4:3, television still hung on to the aging format long after. For decades, the wider formats (1.85 and 2.35) were seen as “movie formats” and 4:3 was seen as a “TV format”. It wasn’t until the early 2000s that 16:9 (1.78) televisions hit the market in masses, and changed the aspect ratio game forever. No longer was widescreen a format only for film, but now it was a television format too.

This of course didn’t immediately make the 4:3 aspect ratio extinct, as there were plenty of legacy systems still running 1.33 programs (some still are), and not every consumer jumped on the widescreen/HDTV bandwagon right away. As the years went on though, it became less and less popular to shoot 4:3, and by the early 2010s it was practically seen as a taboo.

But something has changed in the last couple of years… We’re seeing a resurgence of the classic 4:3 format, with more filmmakers embracing it on feature length narratives. This is something we haven’t seen on a large scale for ages.

Personally, I am (and always have been) a fan of 4:3. Maybe it’s because so many of my favorite films were old classics shot on 35mm or 16mm in 1.33, or maybe it’s the way in which the square-ish frame can inspire unique framing choices. Whatever the case, it’s always caught my attention – so much that I plan to shoot my next film in 1.33 as I think it will be the best choice for the story.

As I’ve been doing some homework and seeking out inspiration for my next film, I couldn’t get over how many contemporary films have turned to 4:3. Obviously 2.35 is still the gold standard, but there’s been a mini explosion of filmmakers that are now embracing the once-taboo format, which I find quite fascinating.

American Honey, Son of Saul, and First Reformed are a just a few of the many features that have recently utilized 4:3/1.33 –

And it’s not just feature films that are benefitting from the format. Television content, music videos, commercials, and even digital projects are using 4:3 in numbers we haven’t seen for many years. So what exactly is it about this aspect ratio that is causing it to have a resurgence right now?

In my opinion, it can be boiled down to a few key factors –

The Democratization of 2.35

It goes without saying that the most popular aspect ratio in cinema today is 2.35. It’s a gorgeous ratio with anamorphic roots, and will continue to be the most common aspect in film for the foreseeable future.

When 2.35 (or 2.39) was first introduced, the technology was reserved for the largest scale motion pictures. This gave the format a certain je ne sais quoi that to this day is associated with bigger budget, higher-end productions. But over the past couple of decades, it’s become accessible to the masses thanks to higher resolution digital cameras (that can easily be masked/cropped to 2.35), cheaper anamorphic lenses, and the general democratization of filmmaking as a whole.

Today, practically every film we see – whether it’s a $200MM blockbuster or a $2,000 micro-budget indie – is finished in 2.35. And while this clearly doesn’t diminish the format in any objective way, I do wonder if the “allure” of 2.35 has worn out with some independent filmmakers. What was unattainable for so long, has now become commonplace… On some level this must be at least one of the (many) factors that’s leading filmmakers to experiment with other aspect ratios.

2.35 used to stand out from the crowd, but now it is the crowd… Which brings me to my next point –

4:3 Differentiates The Work

Around the same time 2.35 became accessible to the masses, so did filmmaking as a whole. Thanks to cheap/free editing software and inexpensive cameras, today the indie film market is flooded with so much content it’s almost impossible to fathom. Everyone with an iPhone and a laptop can (and is) making short and feature films… And while this is incredible in so many ways, it also makes it a lot harder to cut through the noise.

Consider the amount of submissions to film festivals in years past as a representation of how the industry has changed over the years –

According to the graph above (from the Guerrilla Rep), back in 1992 you had about 1 in 2 odds of getting into Sundance with only 250-ish films submitted. That’s a 50% chance! This year, Sundance received over 13,500 submissions, leaving filmmakers with less than 1% odds of getting in.

With such an abundance of content on the market, it’s become harder than ever for filmmakers to differentiate their work. It’s no longer enough to have a good story and strong production values. That may have launched your career back in 1992, but not today. In order for an indie film to stand out in 2018, it needs to be extremely unique, and special enough to rise above the crowd.

So is it any wonder that so many filmmakers are now going against the grain and working with formats (such as 4:3) that were once near-extinction?

Certainly an aspect ratio on its own will never make any film great, or help any film get into a festival. But it does represent the larger notion of doing things differently. This is something that is on every up and coming filmmakers mind right now, so in that respect, it’s no shock that 4:3 is getting a second look.

Vintage Is In

Another big variable right now is that the vintage look is very “in” at the moment. In a recent blog post, I wrote about how motion picture film has seen a resurgence in recent years, so much that pricing on film stock and processing has gone up nearly 30% based on the increased demand. And it’s not just professional celluloid – even Polaroid cameras are back and practically more popular than ever.

Whatever the reason may be, the vintage/throwback/nostalgia look is extremely popular at the moment, and its effect is certainly being felt by filmmakers… Many of whom are employing all sorts of tactics to make their digital footage look a little less 21st century. From the careful use of LUTs to pairing digital cinema cameras with vintage glass and Pro Mist filters, we’ve tried just about everything to get our clinical digital footage to look more filmic.

With that in mind, it’s not surprising that the 4:3 aspect ratio has become a part of this conversation. It’s impossible to deny the nostalgic qualities of the format, which are hard-wired into us after decades of consuming content. In some ways, 4:3 has come full circle – starting out as a motion picture format, later becoming a TV standard, and now returning to its origins in narrative feature filmmaking.

There Is No Better Way To Frame a Face

So far, we’ve touched on some of the superficial qualities that may be drawing filmmakers to 4:3. But at the end of the day, even if a filmmaker is enticed by the vintage look, or the format’s ability to differentiate their work from the next filmmaker, that’s simply an entry point.

What ultimately gets most filmmakers to actually commit to the 4:3 format are the aesthetic benefits – namely framing options. I could write an entire article about how framing is affected by various aspect ratios, and the merits of each format, but for the sake of this post I will focus on just one key factor: Framing faces.

Movies are about people, not landscapes. And unlike epic landscapes (which call for a wide aspect ratio), people – or more specifically, faces – beg for 4:3. The reason is quite simple: A human head fills up more of the frame at 1.33 when compared to 2.35. A normal closeup at 2.35 is going to leave a lot of empty/negative space on the opposite side of the frame. This could of course be an excellent artistic choice for a specific project, but it won’t highlight the actor’s micro-expressions the same way a 4:3 frame will.

There’s something about 4:3 that helps us connect more intimately with the characters. It feels more naturalistic in a sense, and for character driven pieces it can offer an effective gateway for the audience to zero-in on the subtleties of the performances.

There are countless other aesthetic benefits to 4:3 too, not the least of which is how powerful it can be for creating a more boxed-in/claustrophobic look… But we’ll save that for another article.

Final Thoughts

Do I hope we continue to see an increase of 4:3/1.33 films? Absolutely. Do I think for a second it will ever dominate the way it once did last century? Not a chance… 4:3 is definitely having a moment right now, but it still only accounts for a small fraction of the films made today. Even still, I’m happy it’s no longer being seen as taboo, and is yet another creative tool filmmakers feel comfortable pulling out of the toolbox.

The Internet and social media has also opened the floodgates with respect to formats and aspect ratios. Who would have thought 10 years ago the vast majority of home video footage would be shot in portrait mode? Or that the square 1:1 aspect ratio would make such a comeback? Certainly not me… But there is no question that the delivery medium is now influencing the content itself, and 4:3 is a case in point.

I think this has been eye opening for content creators. While many once felt they needed to adhere to certain guidelines (format, aspect ratio, etc.) in order to conform to “professional standards”, we’ve now realized there is no such thing. Sure, most of us will continue to shoot the majority of our work in 2.35, but when a film like A Ghost Story rolls out in a square aspect ratio with rounded corners, we can’t help but find ourselves enamored.

What do you think? Let me know your thoughts 4:3 in the comments below…

For exclusive filmmaking articles every Sunday, sign up for my newsletter here!